Why are we Here?

|

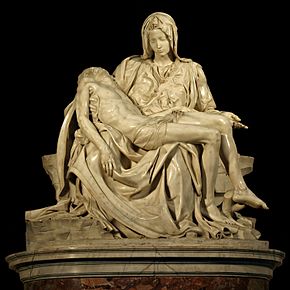

| Michelangelo's Pieta |

I was born on December 14, 1941; 25

days later, on January 8, 1942, a

baby was born to the Hawking family in Oxford England. His

parents named him Stephen. In 1962, I launched my career as a green,

20 year old teacher in a rural school in Saskatchewan; before my

first year was up, Stephen Hawking—then in PhD studies at

Oxford—would begin to fall down for no apparent reason. He was

diagnosed with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. ALS. The dreaded Lou

Gehrig's Disease that robs muscles of potency and renders its victims

totally helpless.

There is no known prevention or cure for ALS.

Even as his physical condition

worsened, Hawking continued his studies, probably taking refuge in

the burgeoning of his mind as his body continued the inevitable decay

called ALS. His amazing thesis on black holes launched him as a

scientific leader who, despite the odds, would advance the study of

cosmology forward by leaps.

It’s astounding to think that

theoretical physics can be done through imagination, even when one

hasn’t the strength any longer to pick up a pair of calipers. Speech must

be delivered digitally, electronically and some of us have become

used to the mechanical, computer-generated voice of Hawking holding

forth on subjects we only partially understand.

PBS recently broadcast episodes from

the Genius series; the one I watched the other day was a brilliantly

done educational presentation called “Why

are we Here?” In it, Hawking explores the tension between determinism and

free will, the idea of parallel universes and, in fact, is

positing the question, “how did we get here?” as opposed to

the burning Christian question, “for what purpose were we created?”

The title of the episode is a bit of a misnomer, seems to me.

I’ll be going to church this Sunday

morning. There a purposeful creation will again be assumed in what is

said and done. The question any Christian must have after watching

Why are we Here? is the same

as thinking believers must have had ever since the church harassed

Galileo into making a false recantation: why can’t the discoveries

of today be added to the wisdom handed down from yesterday? Galileo

and Copernicus asserted from their observations that the sun—not

the earth—was the centre of the known universe. They were right.

What they said was true. How much better would it have been for both

believers and for science if the church hadn’t set theology and

science at odds?

But

it’s not news, I guess, that prophets seemingly have to be stoned

to protect us from the truth. The right question for us might

be—rather than why are we here—“Why

are we so unadaptable to new knowledge?” That was certainly Jesus’

question when he looked down on Jerusalem and wondered how the

population could choose not to gather under the loving wings of God

to be protected like a hen protects her chicks.

However

we understand God, it seems axiomatic to me that he/she is a friend

to truth, not a bulwark against it. It may be true that it was particularly for human perfidy that the word stubborn

was coined.

It’s

an insignificant accident, of course, that Bernie Sanders, Stephen Hawking and I

are roughly the same age, give or take a few days. The significant

observation on that front, though, is that their voices may well prove to have been prophetic. Granted, you and we and everyone who ever was are mere humans, with all the foibles that go along with that. That alone may be reason enough to assert that we are the only species that is plagued by the "Why are we Here?" question.

Comments

Post a Comment